Other related articles

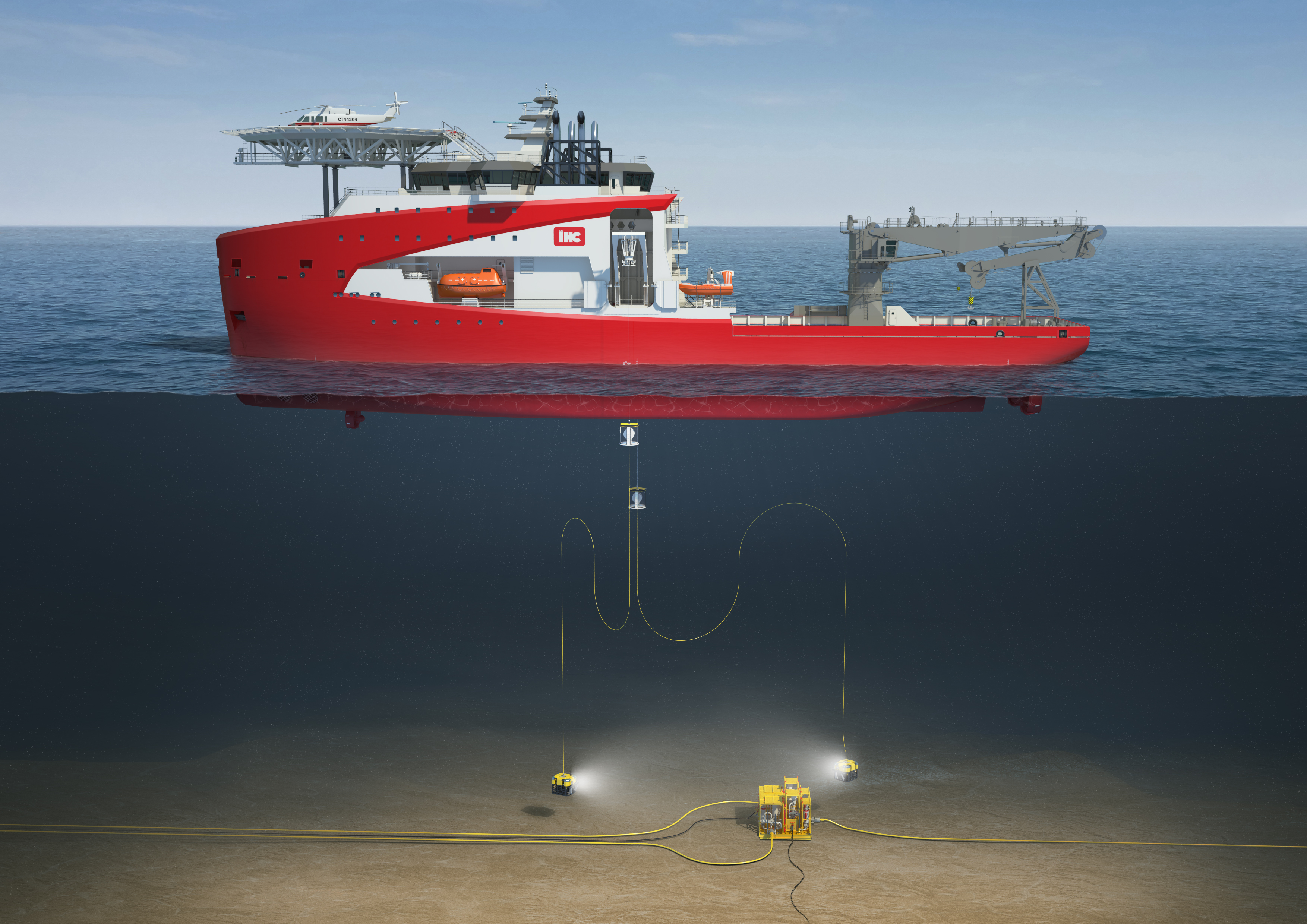

What was Causing the Discharge Pressure to Keep Going High? Dive Support Vessel (DSV) Roller Cone Bits

The SCSSSV Isolation Question

In some wells with surface controlled subsurface safety valves a landing nipple is used to lock and operate a wireline retrievable downhole safety valve. The wireline retrievable valve can be pulled to allow nearly full-bore access to the wellbore, however it is a question as to whether an isolation sleeve should be run or not. One of the key advantages for installing a wireline retrievable subsurface safety valve is that it can be pulled and allow larger tools to be run on wireline. However, the insert valve has to form a seal with the inside of the tubing in a safety valve landings nipple. This is achieved by running an upper and lower seal assembly made of chevron seals (or o-rings) which form a seal for the hydraulic oil in the control line to pressure up the safety valve. When wirelining, the wire will ride in a certain location (low side) and can create a groove in this sealing area. This groove can lead to the packing elements of the insert valve not forming a hydraulic seal and rendering the valve inoperable. In this particular well, there was a history of sand production, and the completion was more than 40 years old, which are both cause for concern when running slickline across a SCSSSV nipple profile. It was decided during job design to install an isolation sleeve across the landing nipple to prevent damaging the sealing profile.

The pulling of the original wireline retrievable surface controlled sub-surface safety valve went easy and had some sand on it when it came out but was in pretty good condition. When running the isolation sleeve it hung up in the tree but landed off nicely in the landing profile (a standard GS running tool was run). The slickline activities were pretty standard - tag for hold up depth, run a bailer, get some samples, see if progress could be made. There is no-one who has spent any time around a slickline unit who hasn’t spent days pump bailing, and this was no exception. The well wasn’t completely cleaned out, but enough progress had been made to expose some perfs and see a slight pressure increase so the decision from the office was to put the well back on.

Pump bailing sand from a well: run / bail / repeatSlicklining is the most inexpensive well intervention method, and it is also one of the most difficult to forecast. The reason slickline is selected is because it is a cost-effective method to determine what is going on in a well and attempt to remediate it. I am always surprised by the manager who is looking for a hyper-accurate time estimate on slickline diagnostics. When a doctor is performing a diagnosis on a patient, this is the worst time to cut costs (providing you want the patient to survive), but many expensive workovers may have been prevented by staying patient with initial slickline operations. I have found a useful tool is to determine a depth where you would expect things to change (based on perfs or logs) and set this as an initial milestone, then as part of the daily reporting, track the change in depth rate. This is by no means certain, as a hard bridge or sloughing goop can slow things down at any time, but at least progress is measured and can give the best possible information, flawed as it is (for more about sand issues in SCSSSV's you can have a look here; www.ballycattertech.com/detail-view-blog/40/completions ). With the slickline depth reached (similar to calling TD), the focus is on resetting the WR-SCSSSV and rigging out. However, things didn’t go as planned – the isolation sleeve wouldn’t retrieve. Multiple attempts, no success, but why? Maybe the wrong probe was being run? – No, we got a good latch and had to shear off every time to release. The sleeve had hung up on the way in, maybe it had dropped off and welded itself into the no-go? Possible, and the tubing was quite old so perhaps the no-go ring had worn large enough that the sleeve was wedged. Pouring over the detailed drawings, it looked like the sleeve was exactly where it was supposed to be, just above the no-go ring and held in the lock – a textbook set.

During well diagnosis is the worst time to cut costsWireline Fishing

After upgrading to braided line, installing an additional cutter valve, and jarring on the sleeve for seven days (the original job was only four days), it finally came to surface. The sleeve was intact, latched into the pulling tool, but it was covered in sand. The debate raged about the properties of formation sand and how it would stick the tool for so long but, when the tool was laid down and cleaned up a new piece of data was found. Along the top of the isolation sleeve was a long scrap in a straight line down the outside of the sleeve. It was as wide as a shear pin, or a grub screw – we never recovered anything metal (and we didn’t get approval for a magnet run) but it looked quite obvious that a piece of metal from sometime in the life of this well had found it’s way on the top of the isolation sleeve. When the sleeve was pulled, the piece of metal got wedged between the sleeve and the tubing, and nothing but a whole lot of jarring was going to separate the two. In an environment where operating costs are of primary importance (which is just about every environment), no-one likes to spend “additional” money on a simple mechanical problem. The worst thing that a cost-overrun situation can turn into is a physical injury – everyone wants to have a successful well intervention, but if tempers flare and the blaming starts, the people doing the work will get distracted by all the drama and then real serious problems can occur. The best professionals I have worked with are those that stay calm when things don’t go exactly their way. The cost overrun term is not correct when evaluating small projects that are custom in nature (i.e. any wireline job), and costs and activities should be looked at a campaign or program level to evaluate the ups and downs of wireline activities. In this situation, the cure was worse than the cause, as more money was spent trying to remove the protection sleeve than in doing the actual job, but does this mean we should never run them? Like a lot of mitigating measures, hindsight is 20/20 and here it may have been better to not run the sleeve, however in other wells I have had difficulty getting a wireline retrievable surface controlled subsurface safety valve to seal after multiple wireline runs. A situation like this highlights the need for accurate record keeping, even in relatively mundane well intervention tasks. Having accurate field measurements of the dimensions of all tools run in setting the isolation sleeve helped rule out possible issues that could have been quite costly to try and fix. When the paperwork is not clear, you hear about it - when it is done correctly you never hear anything. In older wells, which produce solids wireline is a great diagnostic and remedial tool, but it should be made clear that this is an inherently difficult activity to provide a firm time or cost estimate on. The variability in the operating conditions are such that everyone involved in these activities needs to understand that they are at the limit of operating environment for what downhole tools and equipment are designed for. This doesn’t mean never to intervene on these sorts of wells (the benefits can be large), but to not build a false sense of security with a high precision time and cost estimate in an imprecise activity. P.S.; For future wells a modified isolation sleeve was developed with the no-go ring at the top to eliminate space for debris to fall behind.